|

The

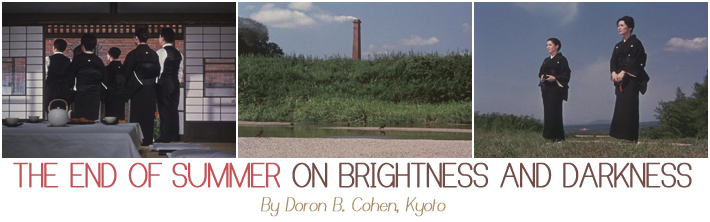

End of Summer - On Brightness and Darkness

By Doron B. Cohen (Kyoto,

Japan)

This

is one of Ozu's most beautiful films to look at,

with constant shifts between bright and dark scenes.

The brightness and darkness are not used as symbols:

the cremation of the old man's body takes place

under dazzling light, while some of the most comic

scenes take place in relative darkness. This is

another of the many ways by which Ozu surprises

his audience, acting against their expectations.

In fact, this is also another expression of Ozu's

realism: in real life terrible things often happen

under the naked sun's light rather than under

the cover of darkness.

The

story is combined of familiar themes: the death

of a parent, the need to marry off a daughter,

the breaking up of a large family, and so on.

But as always with Ozu there are some new twists

and turns, and some new ways of telling, which

we encounter as we become familiar with the Kohayakawa

family, the owners of a small sake brewery,

and with the lives and fortunes of its numerous

members.

The

history of the family - as their chief clerk admits

- is very complicated, and not all the details

are clear. The printed script yields the following

information (revealing also that some of the details

given in Bordwell's book are inaccurate):

The

current head of the family, Manbei, who was an

orphan, married the eldest daughter (name unknown)

of the Kohayakawa family, and was adopted, becoming

the head of the family following his father-in-law.

Manbei's dead wife had two sisters:

The

elder, Shige, married into the Kato family from

Nagoya; she appears when Manbei first has his

heart attack, and also at the cremation.

The

younger, Teruko, is seen several times with her

husband, Kitagawa Yanosuke, "the uncle from

Osaka" who is trying to get Akiko married

to his friend.

Manbei

also has a real brother, Hayashi Seizō, who comes

from Tokyo when Manbei has his heart attack, but

does not attend the cremation (what we see near

the end of the film is not the formal funeral,

which would take place a few days later).

Manbei

had at least three children:

The

elder son, Kōichi, did not want to continue in

the family business and became a university professor.

He married Akiko, who now works at an art gallery,

and had a son, Minoru, but died young.

The

elder daughter, Fumiko, married Hisao, who apparently

was also adopted into the family and runs the

business. They have one son, Masao.

The

youngest daughter, Noriko, who works at the office

of a large company, is yet to be married.

Manbei

may also had a daughter, Yuriko, with his former

mistress Tsune, but the true identity of Yuriko's

father is not clear.

As

often with Ozu films, the story is a constant

play between the older and younger generations.

The focus may be on Manbei and his shenanigans,

but it is also about the marriage of the young

daughter, as well as the possible marriage of

the widowed daughter-in-law. Somehow, in spite

of the large and complex family, everything seems

more simple and concise than in some of the other

films (and with a running time of only 103 minutes,

this film is considerably shorter than most of

Ozu's post-war films). Also, some emotions and

intentions are more starkly exposed than usual:

the lust for life of the old man, the gold-digging

of the mother and daughter from Kyoto, and even

the deep affection between sisters-in-law (played

by Hara Setsuko and Tsukasa Yōko, who played mother

and daughter in a similar situation in Ozu's former

film). This affection is expressed through the

careful use of one of Ozu well-known means of

telling-through-showing: the action in unison.

We see the two women squat and rise as one, as

a sign for their deep mutual understanding and

same-mindedness.

The

End Of Summer is one of only three films that

Ozu made for companies other than his home studio,

Shōchiku. This one was made for Tōhō,

using that studio's staff rather than the usual

people who worked with Ozu in most of his post-war

films (and in some cases, also pre-war ones).

Perhaps this also explains the appearance of many

unfamiliar faces among the actors and actresses.

Only three of Ozu's regulars appear here (Hara

Setsuko, Sugimura Haruko, Ryū Chishū), as well

as a few actors who appeared in only one other

film (Nakamura Ganjirō, Tsukasa Yōko, Naniwa Chieko,

Katō Daisuke, Mochizuki Yūko), but many appear

only in this film, and must have came from Tōhō's

stables. Some of these one-timers give a truly

wonderful performance: emotional but confident

(Aratama Michiyo as the elder daughter Fumiko),

slightly comical (Sazanka Kyū as the chief clerk),

or farcical (Morishige Hisaya as Akiko's hapless

suitor).

According

to Donald Richie, in his groundbreaking book about

Ozu (p. 63), in this film Ozu went a long way

to accommodate actors' wishes: Mochizuki Yūko,

a famous actress who earlier had a short scene

in only one of Ozu's film wanted to be in another,

and Ozu's regular actor Ryū Chishū also

had to be fitted in somehow, so Ozu added the

scene of the farmer husband and wife commenting

on the cycle of life towards the end of the film,

a scene that many critics had found superfluous.

And on the lighter note, this is probably the

only Ozu film with the participation of gaijin

(foreigners), in the figures of "George"

and "Harry", Yuriko's boyfriends; their

real identity is unknown, and they get no mention

in the titles.

The

film ends on a somber note, with crows perching

over tombstones, but we must remember that earlier

we heard that Noriko is going to marry the man

she loves, and a new life begins for her. Akiko

also has her choice of going on living as she

pleases. While everything has ended for the old

man, not all is dark.

©

All rights reserved to the author

|