|

Early

Summer - Poetry in Motion

By Doron B. Cohen (Kyoto,

Japan)

Ozu

is famous - or notorious - for his static camera.

In fact, in his later films he dispensed of camera

movements all together, but his art did not seem

to have suffered by this loss. However, when the

camera did move, magic often happened.

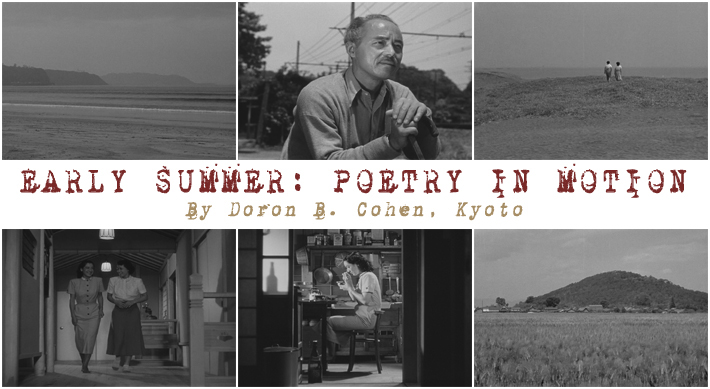

In Early Summer Ozu still used tracking

shots relatively often, and a few of those shots

are truly unforgettable.

The

film opens with a shot - from a static camera

- of gentle waves breaking against the shore in

Kamakura. We then move gradually into the house

of the Mamiya family, situated not far from that

shore, getting to know its seven members one by

one as they go through their morning routine.

The main concern of the family is soon made clear

with the visit of the rustic old uncle: the need

to katazuke the youngest daughter, Noriko,

who will soon be past the marrying age. The meaning

of katazuke that first come to mind is

"tidy up", "clear up", or

"clear away", but it also means "give

/ dispose of one's daughter in marriage".

Perhaps these associations of meaning do not sound

strange to the Japanese ear as they do to the

foreigner's, but still, the daughter's reluctance

to get disposed of by marrying the family's choice,

a bachelor 14 years her senior, is understandable.

She acts independently and ends up choosing her

partner without the family's consent, but her

rebellion is a mild one: after all, she's marrying

the neighbors' son, who was the best friend of

her missing brother, and she will join him and

his little daughter in remote countryside, where

he will head a hospital ward. On second inspection,

she is perhaps more "traditional" than

"modern", as even her best friend Aya

is surprised to realize. She also follows her

heart, as would other young women in Ozu's subsequent

films. Her marriage causes the household to split

three ways, but that's the way of the world, and

would have happened sooner or later, as the old

father tells her kindly. In an earlier scene we

have seen him going out of the house, stopping

at a train crossing, sitting down, waiting for

the train to pass, and not hurrying to get up

again once it does: he realizes life is passing

him by, but he accepts it with no great ado.

Much

has already been written about the camera movements

in this film - mostly by David Bordwell in his

extensive book about Ozu - so there is no need

to analyze theme once again, perhaps only mention

a few of them shortly: the breath-taking shot

on the sand dune, in which the camera seems to

detach itself vertically from the hold of the

earth's gravity; or the last, dizzying shot, in

which the village and mountain remain solid in

the middle of the frame while the camera travels

over the barley fields (the original title of

the films also means "barley harvest season"),

echoing the sea in the first shot. These and other

sequences in the film are pure poetic moments,

created by a cinematic artist at his peak. But

notice should also be given to how Ozu's playfulness

and humor are enhanced by the use of camera movements

and editing. For example, we see Noriko and her

friend Aya tiptoe down a corridor towards the

camera, which tracks back as they advance; then

the angle is reversed and the camera is tracking

forward, but rather than seeing the two from behind

as we would have expected, we find ourselves back

in the family's house, going towards the kitchen.

This method of cutting and editing was already

used once earlier in the film, and would be used

again even in some of the later films. From cinematic

point of view, Ozu is often the master of the

unexpected: he would not show us what we expect

to see, but rather hide something from us, or

skip forward to a different point in time or space.

In the above example what we expect to see but

are not shown is what the two friends actually

saw when they picked into a room where the man

Noriko would not marry was having dinner. Our

curiosity about him is not to be satisfied. We

see, instead, Noriko coming back home to a cold

welcome by the family, having her solitary dinner

in the kitchen, but steadfastly standing her ground.

Apart

from the story, rich in humanism and relevant

beyond its specific time and place, Early Summer

can also be viewed as a historical document reflecting,

sometimes inadvertently, the reality of life in

post-war Japan. Almost every scene in the film

contains treasures of social information. For

example, reflecting on the old uncle's previous

visit, which took place a few years earlier, not

long after the end of the war, Fumiko tells her

sister-in-law Noriko, "I was still wearing

monpe then", referring to the baggy

work pants that women had to wear during that

period of austerity. By now (1951) the situation

has improved considerably, and the women can once

again wear kimono or skirts, and occasionally

even indulge in shortcake, in spite of its prohibitive

price. Later, in one of the last scenes, Aya warns

Noriko that if she will indeed go with her chosen

spouse to Akita, she will have to wear monpe

- apparently those remote, rustic parts of the

country are not enjoying yet the new-found prosperity

of Tokyo. But Noriko says she certainly will wear

them, demonstrating once again her resolution

to persevere on the path she has chosen, even

if it means giving up all luxuries of modern life

in the big city, for the sake of accompanying

the man with whom she believes she could be happy.

Many more such instructive moments occur in this

great film.

Among

Ozu's films, Tokyo Story is usually considered

his great masterpiece, appearing on various lists

of "10 Greatest Films" and so on, but

Early Summer is a masterpiece of no lesser

quality, and in some cinematic and thematic aspects

is even richer than the more famous film. I tend

to regard Ozu's oeuvre as a unity, but when pressed

to name his best realized or most representative

films, Early Summer will always come to

mind as one of his greatest achievements.

©

All rights reserved to the author

|